Molecular diagnostics and modern lab workflows are pushing plastic components into tougher territory: smaller fluidic features, tighter repeatability, cleaner handling expectations, and faster ramps to volume. All adding to the challenges of using high-performance polymers in medical manufacturing. That’s why the most important question isn’t simply:

“Can this be molded?”

It’s: “Can this be injection molded repeatably, inspected reliably, and scaled confidently-without redesign loops?”

When working with high-performacce polymers in medical device and part manufacturing, you must start early in the process. High-performance thermoplastics (and optics-focused medical polymers) can unlock chemical resistance, thermal stability, and mechanical performance-but they’re also less forgiving when geometry gets complex. The good news: you can de-risk moldability early with a structured set of checks before you commit to production tooling.

Why moldability matters more than ever in diagnostics and lab devices

Diagnostics parts (cartridges, microfluidic components, cuvettes, sample-handling consumables, instrument interfaces) tend to stack constraints in one design:

- Micro-features that must replicate consistently to maintain flow, mixing, or assay performance

- Optical performance for detection windows, clarity, and low background signal

- Chemical compatibility with buffers, reagents, surfactants, and cleaning agents

- Dimensional stability across thermal zones (incubation, heated stages, cycling)

- Manufacturing hygiene + traceability expectations that demand process control and consistent documentation

In other words: “moldable” must also mean scalable, stable, and controllable.

Step 1 – Start with the real use case (diagnostics changes the rules)

Before material selection or DFM tweaks, lock down what the part actually experiences.

Chemical exposure

Document the real chemicals: reagents, buffers, detergents/surfactants, disinfectants, solvents (as applicable), and sample matrices. From an engineering perspective, the risk is not only bulk compatibility-it’s also stress cracking, extractables/leachables considerations, and surface interactions (adsorption of biomolecules, surfactant effects) that can change assay behavior.

Optics and detection

If the instrument reads light (photometric, fluorescence, imaging), polymer choice and surface condition become performance parameters. Many diagnostics programs evaluate COC/COP for optical clarity, low moisture uptake, and good feature replication-while still managing molding stress/optical artifacts and cosmetic requirements.

Thermal profile

Heated zones and thermal gradients can shift critical features through differential shrink, creep, or assembly stress. The more demanding the thermal profile, the more you should treat polymer selection + wall strategy + gating/cooling as a coupled system.

Handling and cleanliness

Even for non-implants, diagnostics manufacturing often requires tight control of particulates, cosmetic defects, and traceability. These requirements should influence CTQs, inspection approach, and packaging/handling strategy.

Step 2 – Confirm the resin-to-geometry match (not all “high-performance” plastics mold the same)

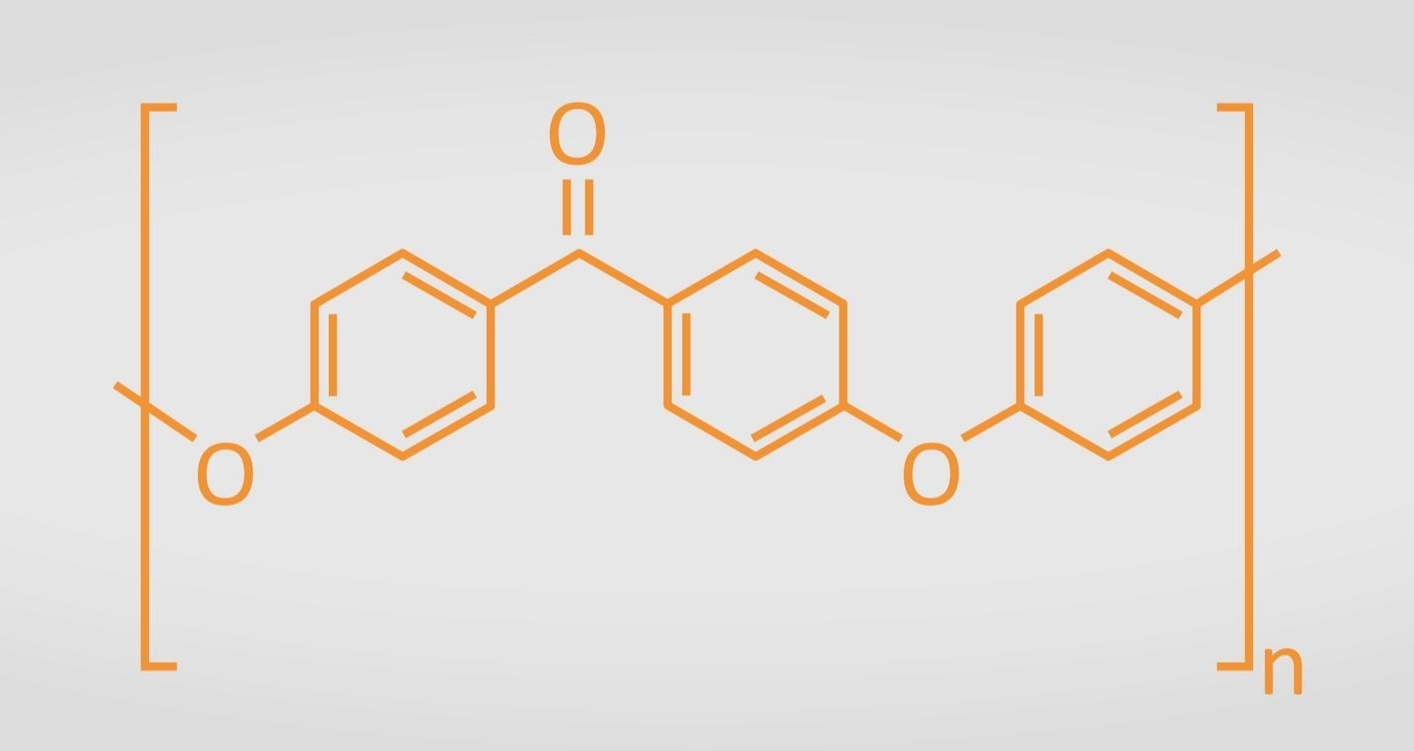

Even within a polymer family, grades vary widely in viscosity, shrink, crystallinity, and optical behavior. As you shortlist candidates (commonly medical-relevant options include PPSU, PEI, PEEK, PC, COC/COP, and others depending on requirements), sanity-check:

- Flow / viscosity reality: Can the material fill your thinnest sections and longest flow lengths at a reasonable process window (not “barely fills at the limit”)?

- Shrink + warp tendency: How sensitive is the part to orientation effects, wall transitions, and cooling rate differences? Semi-crystalline materials (e.g., many PEEK grades) often bring higher shrink sensitivity than amorphous polymers; fiber fill can amplify anisotropy.

- Moisture and conditioning: Does the polymer require controlled drying? How does moisture affect viscosity, hydrolysis risk, and part properties? (For some high-temperature polymers, moisture management is not optional.)

- Optical/stress behavior (if relevant): Can the design tolerate birefringence, flow lines, weld lines, or stress whitening? Optical requirements should be considered during gating, flow path, and surface spec decisions.

A practical engineering lens: choose the material that meets requirements with the widest stable molding window, not the one that barely meets requirements with a fragile process.

Step 3 – Run a “CAD reality check” before committing to production tooling

A fast screen of the CAD catches the biggest molding risks early.

Walls and transitions

Aim for consistent wall thickness. Abrupt thickness changes drive differential cooling, which drives sink, warp, and dimensional drift-especially painful for microfluidic performance and tight instrument interfaces. Use smooth transitions and radii wherever function allows.

Flow challenges (micro features, long flow lengths)

Thin walls + long flow length + micro-features raise sensitivity to:

- venting (air traps)

- weld/knit lines

- shear heating and viscosity changes

- pressure drop and incomplete fill

Flag “risk zones” early (long narrow paths, sharp turns, isolated pockets) so you can address them with geometry, gating strategy, or tool design choices.

Draft and parting strategy

Draft is not a late-stage cleanup item-late draft changes cascade into assemblies and seals. Plan parting lines away from:

- optical windows

- sealing lands

- precision datums and interfaces

where flash/mismatch becomes functional risk.

Complexity decisions (actions, shutoffs, fragile features)

Undercuts and actions aren’t automatically wrong, but each adds variability and maintenance complexity. Likewise, fragile shutoffs/knife edges can drive flash and wear over time. If a feature forces complexity, it should be tied to a real functional need-and evaluated against yield and long-term robustness.

Step 4 – Define CTQs early, and design for measurement

Diagnostics programs often lose time when parts “meet print” but fail in real use: they don’t seal, they don’t assemble consistently, or they introduce read variability.

Define:

- CTQs tied to performance (flow features, seal geometry, optical zones, alignment datums)

- a datum strategy that reflects how the part is functionally located in the device/instrument

- a measurement plan that can verify CTQs repeatably at production cadence

Engineer’s rule of thumb: if you can’t measure it consistently, you can’t control it consistently.

Step 5 – Use simulation + tooling strategy to reduce unknowns

Modern teams don’t wait for first trials to learn fundamentals. A practical analysis plan can help predict hesitation, weld lines, air traps, and warp trends. Then align tooling strategy accordingly:

- Gate selection and location influence weld line placement, packing, cosmetics, and stability in critical regions

- Cooling strategy is often the difference between “works on a good day” and “stable across lots”

- Venting is essential for consistent fill-especially in micro-featured diagnostics parts

This isn’t about perfection-it’s about eliminating surprises that would otherwise surface late.

Step 6 – Prototype the risk, not just the shape

For diagnostics, prototypes should answer the questions most likely to derail scale-up: dimensional stability, repeatability, sealing behavior, optical performance, and assembly alignment.

- Plastic machining: fast iterations for fit/handling and early device learning (with the caveat that machining won’t reproduce molded stress/flow artifacts).

- Prototype tooling: best for validating real molding behavior, weld lines, cosmetic/optical risk, and the practical process window.

Where EPTAM’s plastics expertise fits: turning “moldable” into “shippable” for medical device manufacturing

De-risking moldability works best when plastics decisions are made with the full workflow in mind-DFM, tooling intent, molding, inspection, and (when applicable) sealing interfaces.

EPTAM supports medical device and diagnostics programs with:

- Thermoplastic injection molding (production-minded DFM and scalable repeatability)

- Plastic machining (rapid iteration and bridge strategies that preserve production intent)

- LSR molding when compliant sealing features are part of the system and must be engineered alongside rigid plastic geometry

The practical benefit isn’t “one-stop shopping” as a slogan-it’s fewer interpretation gaps, faster feedback loops, and tighter quality ownership across the plastics build.

Quick pre-tooling checklist for diagnostics teams

Use-case confirmed (chemistry, optics, thermal exposure, handling needs)

Resin shortlist aligned to geometry and process realities

Walls/transitions reviewed; flow risk zones identified

Draft and parting strategy avoids optical/sealing/critical interfaces

CTQs, datums, and measurement access defined early

Analysis + prototype plan targets the highest-risk unknowns

Closing thought

High-performance polymers in medical manufacturing and thermoplastics can enable outstanding outcomes in molecular diagnostics and lab automation-but they “fight back” when geometry pushes the limits by narrowing the stable process window. The modern path is to de-risk early: align requirements, resin behavior, DFM, tooling strategy, and validation planning before production tooling locks decisions in place.